Reviewed by Sheana Ochoa

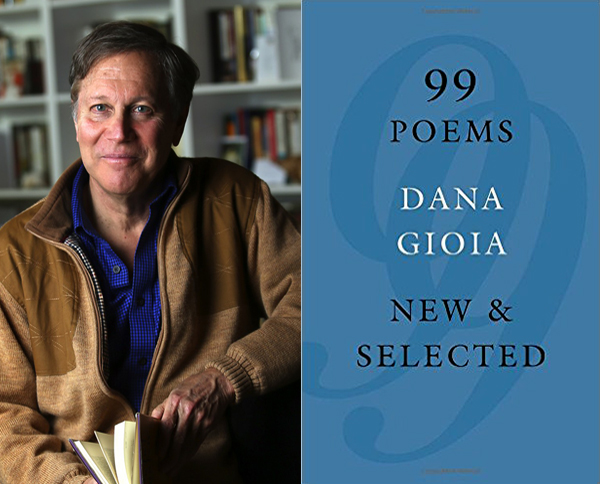

California’s Poet Laureate, Dana Gioia, reads from his new collection this Sat., Nov. 19, in SLO.

The language of 99 Poems seeks the universal

— From its earliest incarnation as an aural art form, poetry has been praised for revealing universal truths. California Poet Laureate Dana Gioia’s 99 Poems: New and Selected takes this most sacred of the poet’s tasks to heart. Yet, it isn’t so much Gioia’s talent at revelation that marks his poetry, but the way he uses every day language to infuse his work with realism, which — in his own words from his essay “What Is Italian-American Poetry?” — “reflects a concern with portraying a world of common experience rather than the creation of a private verbal universe.” These aren’t poems that need to be unlocked or read several times over in order to grasp. Rather they are like an open house: inviting, well appointed, and — following a tradition Gioia himself defines as thematic of Italian-American writers — public.

Take the poem “Insomnia” in which Gioia uses the second person, putting the reader in that “twisting in the sheets,” feeling of not being able to fall asleep: “Now you hear what the house has to say./ Pipes, clanking, water running in the dark,/ The mortgaged walls shifting in discomfort.” The poem describes the sleep-starved “you” listening to the house, an activity we find at poem’s end only renders “useless insight.”

Gioia is a master of endings. We read to get to his promised pay off.

The literary tradition of writing in the language of plain folk traces back to Gioia’s campeasano Dante in the epic poem Divine Comedy. Gioia’s “Pity the Beautiful” is chalk full of prosaic, everyday language: “Pity the beautiful,/ the dolls, and the dishes,/ the babes with big daddies/ granting their wishes./ Pity the pretty boys, the hunks, and Apollos,/ the golden lads whom/ success always follows./ The hotties, the knock-outs,/ the tens out of ten,/ the drop-dead gorgeous,/ the great leading men.”

The poet with his favorite cat (photo Star Black).

Gioia’s vernacular, his use of the ordinary creates a hospitable playing field on which to explore the central theme of 99 Poems, that of the great paradox of human nature: our desire to be joyful, but our inability to do so. “Being happy is mostly like that. You don’t see it up close./ You recognize it later from the ache of memory.”

The book opens with the poem “The Burning Ladder,” which describes a Jacob, not unwilling to climb the ladder, but unaware of its very existence. He misses out on a heavenly ascension because he is asleep: “a stone/ upon a stone pillow,/ shivering. Gravity/ always greater than desire.” The poem sets the stage for a world whose subjects miss the mark, fall short, and fail to realize or take advantage of their potential. Some of Gioia’s subjects are oblivious to this failing, while others, such as the narrator in “Interrogations At Noon,” ruminate on “the better man I might have been,/ Who chronicles the life I’ve never led.” In “The Road” the narrator “sometimes felt that he had missed his life/ By being far too busy looking for it.” This central theme that highlights our inadequacy is not a means in itself. It serves a purpose.

The existential dread in 99 Poems is cautionary, the point being “To learn that what we will not grasp is lost.”

It can be said that poetry either laments or celebrates, and 99 Poems is no exception. While the dilemma of the human pageant weaves through the book, so does a celebration of place and love and mystery, all words Gioia uses to divide the sections (seven in all) of his book. In “Vultures Mating” we find that “desire brings all things back to earth,” and we marvel with a hiker going to “the end of the world” where he “looked downstream. There was nothing but sky,/ The sound of the water, and the water’s reply.”

In these celebratory poems as much as in the poems of lamentation, we remember the poet’s power to both reveal the depths of our soul-sickness and the heights to which our spirits soar.

Hear Dana Gioia read from 99 Poems in the 33rd Annual San Luis Obispo Poetry Festival, this Saturday, Nov. 19 , 2-4 p.m., at the San Luis Obispo County Library, 995 Palm St., San Luis Obispo 93403.